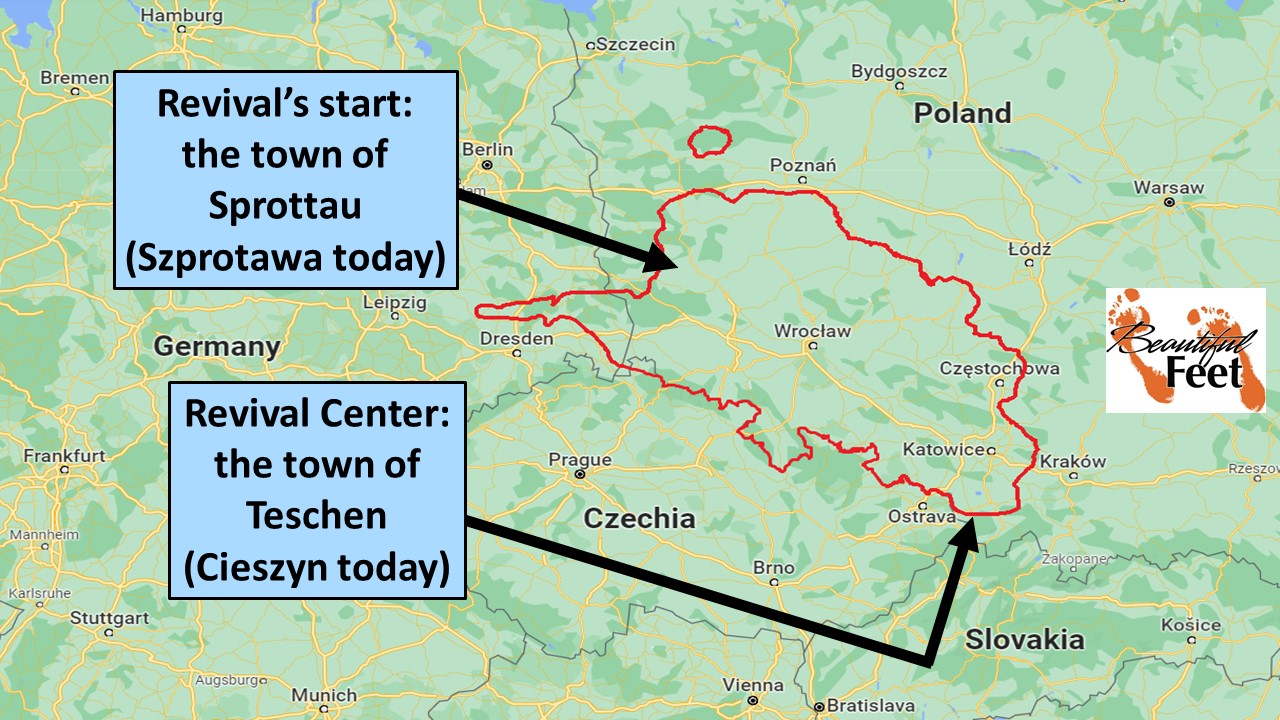

This map shows the region then known as Silesia, along the border between Poland and Czechia.

Introduction

In 1708, along the Poland and Czechia border, in the area then known as Silesia, there was a revival that commenced, starting among children. The historical backdrop to this revival is painted with many wars, most of them religious in nature.

Much of the contention was between the Lutheran and Catholic states. Thrown into this mix were the emerging Pietists, a movement from within Lutheranism.

The Pietists, though still claiming to be Lutheran, had a preference to meet in small groups outside the confines of the established Lutheran Church, in what was referred to as conventicles (which civil authorities outlawed in some areas). These were nothing more than secret or public gatherings for worship—similar to the disciples meeting privately in the Upper Room or in private homes for worship, in lieu of worshipping at the synagogues.

The established Lutheran Church strongly opposed these meetings, which were out from under the Lutheran Church’s supervision and control.

The children associated with this revival were associated largely with the Pietists. The religious power brokers that were vying for control, often enforcing restriction on the Pietist worshippers, created the impetus for the emergence of this Children’s Prayer Revival.

Religious Oppression

In the 1500s, Silesia was about 90 percent Protestant. But with the transference of political powers there was a movement toward reestablishing Catholicism in the region. Much of the impetus behind the revival came from the heavy oppression placed upon Protestants by Catholics. The Catholic Hapsburgs had systematically been weakening their “opposition” through:

► Church reduction policy, which occurred throughout the 1600s.

► Closing over 1,200 church buildings.

► Closing of Protestant schools.

► Protestant children were forced to go to Catholic schools.

► Exiling Protestant pastors and their families.

► The evangelical faith was made illegal, as was possessing a Luther Bible and evangelical literature.

► The Jesuits were said to have been “church-political storm troopers.” In the town of Freystadt, 30 families with 56 children, identified by Jesuits as evangelical, were given 3 months to convert to Catholicism or their belongings would be sold.

► The travel to churches across the border into Saxony, Bohemia or Moravia (Germany and Czechia), was forbidden.

This religious persecution led to:

► Clandestine prayer meetings.

► House churches.

► Church services held in the mountains, forests, or open fields.

► Travel to border churches to worship—which involved traveling long distances to hear a sermon and worship in a church building.

► Laity-led churches and prayer meetings.

► Silesian spirituality had as its basis the authority of the Bible (sola scriptura) and it represented a challenge to Catholic traditions.

Extraordinary Prayer

This revival commenced with extraordinary prayer, around December 28, 1707, on Holy Innocents’ Day. The location was the Silesian mountains, in the town of Sprottau—an area where evangelical worship had been outlawed for fifty years. It was here that children, boys and girls ages 4-14, assembled three times per day in the open fields outside the town to pray (7 a.m., around noon, and around 4 p.m.).

Some of these meetings would last 3-5 hours.

The children’s custom was that they would form two large circles and pray. The inner circle contained the boys and the outer the girls. Often they would kneel, and sometimes they lay prostrate. They would sing Lutheran hymns, read Psalms and devotional texts, and close with a blessing. These children seemed to be immune to the fear their parents had of doing the same. The church leaders were incensed that prayer was taking place outside the church building, yet it was as if nothing could stop these children from assembling to pray.

One father, concerned about their children defying the church and governmental authorities, tried to lock his son and daughter in their rooms. Yet when he heard that they intended to leap out their window to assemble for prayer, he conceded and permitted them to go.

The Revival Spread

Before long the adults joined with the children as they united for prayer. When the adults witnessed the children singing and praying, it powerfully affected them and “melted them to tears.”

In a few of the towns the numbers of children that assembled reached between 300 to 1,000.

The government authorities commanded the gatherings to stop but the children would not. At one location a hangman was sent with a whip to disperse the children who were meeting in the marketplace. But when he saw them praying, he was so moved by what he witnessed that he could not do it.

Much to the irritation of the non-Pietist Lutheran clergy, supernatural occurrences arose. When these would happen, they preferred not to talk about them. There were occurrences such as:

► When a cavalry troop—trying to intimidate the children—pretended to charge them, the children showed no reaction and continued with their prayers.

► The children were shot at with guns “without ball” [blanks], but they were not at all frightened.

► Letters from the prayer books used by children began emitting light.

► Doves were flying around the children, close enough for them to be touched.

► It was reported that children also had dreams and visions.

At Breslau, Roman Catholic children joined the Lutheran and Pietistic Lutheran children for prayer, even though strict orders were in place for the parents to keep their children at home. All the while these children would assemble to pray, and thousands of both Lutheran and Catholic adults would assemble to observe.

This passion for prayer spread like fire. Within five days this prayer revival among children was witnessed in 5 different principalities of Silesia. A contemporary of that era, Johann Wilhelm Petersen, said of this rapid spread:

…The prayer of the children spread into five different principalities of the land of Silesia within approximately five days. If at the same time a fast-moving wind storm, a typhoon, developed and came on so fast and was moved as by a hand, without a hidden divinity we can not conceive such an impulse.

A Spontaneous Movement or a Spreading Movement

The documented reports indicate that the Children’s Prayer Revival didn’t really spread, but that it was spontaneous, being driven by an impulse of God. The reason for that thought was due to the children’s prayers being said to have spread throughout Silesia in only 5 days, and that without any communications among them. The children’s prayer groups throughout the region also used the same routine for prayers, which indicated that it was the hand of God driving the movement.

When asked who put them up to these prayer meetings, the children said that they did it “of their own accord.”

Some locations witnessed groups of 3,000 – 4,000 assembling to pray, even so, the gatherings were very orderly and well conducted.

There is scarce a village in Ligniz where they go—every day assemble in the open air in the greatest tranquility and deepest introversion of mind…, to hold hours for praying which is practiced upon the mountains and other places. Some of the ministers do behold and wink at this practice, others rage against it, and very few are pleased to see it. – Heinrich Wilhelm Ludolf

Some observations made about these children and their prayer gatherings:

► They were not given directions on how to conduct these prayer gatherings.

► They acted out of their own inner desires, and they often couldn’t wait for the next time for prayer.

► They were said to have had such a love for prayer that they forgot everything, including sleeping and eating.

► The weather was never so bad that it would deter them from assembling.

► Children that previously were wild and troublesome and that had to be dragged to church, could not be kept away from the prayer gatherings.

► The children’s behavior was noted to be far above their ages, as they were extremely disciplined. It was described as “an uncommon devotion.”

► The children would act against the orders of civil and parental authorities when they were told not to pray.

► They would choose a reader among them who would stand in the middle of the circle and who would then lead in songs and prayers.

► They overcame threats and hindrances that were trying to stop them.

► In the open air, these prayer gatherings were held outside the villages, towns, and cities.

► They were mostly on their knees the entire time they prayed.

► They would often prostrate themselves on their faces.

► When ministers would attempt to lead in the children’s prayers, the children would disapprove, because they said that the ministers wouldn’t pray long enough.

► Typical gatherings would include:

- Seven songs

- A prayer between each song

- Reading of a Psalm of repentance

- Often the prayer for their churches to be given back to them, which the Catholics had taken away

- Reading of a chapter from the Bible

- Conclusion involving lifting hands together and singing two more songs, then the reading of Numbers 6:24-26

All opposition to the Children’s Prayer Revival came from the Catholics and Lutheran Orthodoxy, while the Lutheran Pietists were positive toward the movement.

Adults who had documented the prayers of the children said that they asked:

► For forgiveness

► For better understanding of the Word of God

► That God would send His Holy Spirit on the people

► That God would send revival

► That God would favor them

► That they might become messengers for God

One Fault

If there was a fault to be laid upon the children, it was that they would at times carry stones to throw at those who would attempt to stop them in their prayers.

This image has the ruling authorities at this time (Joseph I Holy Roman Emperor; and Charles XII of Sweden). Under their image can be seen two circles of children praying, with a leader in the midst of the circle.

The Revival’s Center

The Children’s Prayer Revival became the catalyst for revival and renewal throughout the churches, and even though the revival’s origin commenced in the northern part of Silesia, it made its way throughout the region, with the very southern town of Teschen (today Cieszyn) becoming the revival’s hub, and its influence became felt throughout central Europe.

Jesus Church (the Lutheran Jesuskirche church in Teschen, now Cieszyn), was one of the churches that the Catholics allowed the Protestants in the region to have, though the money for the church’s support had to come from personal donations, which was opposite of how the Catholic churches were funded. The Catholic churches received their support from the state.

People would walk throughout the night to arrive at Teschen to participate in the services. Thousands gathered, both inside and outside the church, with many spending hours in prayer and fervent singing of hymns.

Pietist pastors were invited to come to Teschen to oversee what the Lord was doing. Even though the church in Teschen, with its multiple balconies, could accommodate 5,000 people, it was so inundated with worshippers that services began at 6 o’clock on Sunday mornings and continued throughout the day, being conducted in various languages (German, Polish, and Bohemian, or Czech). The number of weekly worshippers reached 40,000.

People outside the church invested their time in prayer, confessions, and passionate singing of hymns. What began as groups of children in the open fields, turned into a movement that spread throughout the surrounding region.

Discipleship

In our present era many churches have no plan for how to disciple new Christians. Yet, during this revival there was pastoral care that was initiated immediately after a person’s conversion. Because of this care, new converts were able to receive communion in only eight days after conversion. This was because there were special classes to prepare them for taking of communion. In addition to those classes, there were many other special Bible classes scheduled, as well as a full schedule of prayer meetings.

Attacks Against the Revival

Arthur Wallis, in his book In the Day of Thy Power, stated that

If we find a revival that is not spoken against, we had better look again to ensure that it is a revival. —Arthur Wallis

Some pastors wrote that the “Children’s Prayer Revival” was the work of man, or that it was the work of the devil.

Why the Attacks

► Catholics feared their political power would erode.

►The Lutheran clergy, who were opposed to Pietism, were so adamant that they colluded with the Catholics to renounce the revival.

► Non-Pietistic evangelical clergy would rather have seen an end to the most successful outreach witnessed in Silesia than have it tinged with Pietism.

► One pastor said that “many of the clergy in Silesia raged against the revival.”

► Demeaning labels were attached to those who joined themselves to this revival. Names like Quakers, Pietists, and even Heathens.

► The movement was labeled heretical because prayers were being conducted outside the church building. If it were inside, under the control of the clergy, it would have been acceptable.

► When the children were asked about their being forbidden to pray in the churchyard, they answered the question with a question:

Why he [the minister] would not suffer ‘em to pray in the Church-yard, and yet suffered ‘em formerly to play with marbles and balls in the very same place?”

Revival Spread from Children to Adults

As adults gathered to observe the wonders of their children praying, everything came to a standstill, and it wasn’t long before they also entered into what God was doing. For several decades after this revival its power was still being felt, even leading up to the founding of the first Protestant denomination that had missions as its core—the Moravian Church (1727 Moravian Revival).

Results of the Revival

► Revivals of children praying emerged several times during the following decades.

► God used the “foolishness of these children” against the wisdom of this world. In fact, their prayers turned many people’s hearts to God.

► Some of the previously worst-behaved children became leaders of prayer groups, and the children paid as much attention and reverence to the leader of their group as they would a minister.

► The children became more willing than ever to go to school, even though previously there was a great disinterest with education.

► The regenerating work of the Holy Spirit was seen on a mass scale.

► The children’s prayers were said to have “awakened the people,” and that they had “power in the supernatural battle between good and evil.”

► The ale-houses (bars) were often empty, being “little frequented,” and in some places all of them were closed.

► Not only were more and more children “awakened” as the movement spread, but many adults in the crowds who gathered to watch them were weeping, reflecting, repenting, and being awakened.

► Letters written by eyewitnesses of the Children’s Prayer Revival were circulated throughout Europe.

► With the translation of these eyewitness reports into English, in the form of Praise Out of the Mouths of Babes…, Great Britain and all of its colonies also received the news, giving inspiration to thousands of readers.

After the senior pastor at Jesus Church in Teschen translated Jonathan Edwards’ A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God, parallels between what God did in New England and Silesia were observed.

(Note The First Great Awakening)

Caspar Neumann (1648-1715)

Rev. Caspar Neumann

Caspar Neumann, the chief Lutheran clergyman in the city of Breslau (today Wroclaw), was a vocal opponent of the Children’s Prayer Revival, yet in his eyewitness account of the revival he had many good things to say. We quote him here with our translation from the old English:

God is pleased to visit our country in such a manner as was never heard of. For what a strange and unaccountable thing is it, that children of a whole country should rise, and show their disobedience therein,

that they will pray in sight of all opposition;

that they will pray in the eyes of all the world;

and that they will pray more than can be desired or allowed of;

whereas commonly children must be compelled to pray with a great deal of labor.

The thing is so hard, and contrary to common sense, that no man with all his power and cunning could have been able to produce such a universal insurrection for prayer, such an uncommon zeal to pray, that children forget their very eating and sleeping, some waking almost all night, out of an eager impatience; and some fasting till night, that they may be the better able to pray. So much patience in frost and cold, and in the most troublesome weather; such an unshaken constancy, modesty, and order observed by most of them at their hours of prayers; the ready obedience they yield to their companions, ruling sometimes over them, severely enough; the earnest devotion of most of them, the like whereof is scarce met with amongst old people; the answers made by some, when they were called to an account, so that one had cause enough to wonder at their sense and understanding; their sending deputations and messages to the magistrates and to the clergy, for having advice and assistance; and the last, the never heard of zeal and anguish, even to the swooning away of some, when kept by force from their hours of prayer. All these things are so unusual in youth, and so strange in my eyes, that I must leave it to God’s judgment, and suspend my own.

Sources

► Kinderbeten by Eric Jonas Swensson

► Praise out of the Mouth of Babes, or, a Particular Account of Some Extraordinary Pious Motions and Devout Exercises, Observ’d of Late in Many Children in Silesia by Anonymous

Return to List of Revival Stories

Chet & Phyllis Swearingen:

Office: (260) 920-8248

romans1015@outlook.com

Beautiful Feet

P.O. Box 915

Auburn, IN 46706