Revivals During the Civil War in the United States

Introduction

The most-watched PBS program, with more than 39 million viewers who saw at least one episode and viewership of more than 14 million who watched each episode, was The Civil War miniseries. Though the revival that took place during this war was extensive, dramatically impacting military and civilian life, it was never mentioned in that miniseries—even though there were hundreds of thousands of conversions during the war.

Deliberate Omission by Religious and Secular Historians

One could assume that the omission of such a well-documented awakening, impacting hundreds of thousands, was deliberate and intentional. Not only is the account omitted in the PBS miniseries, but in almost all books written about the Civil War, there is very little, if anything, that is written about the dramatic impact the revivals had on soldiers during the war and on society afterwards.

Godless Military

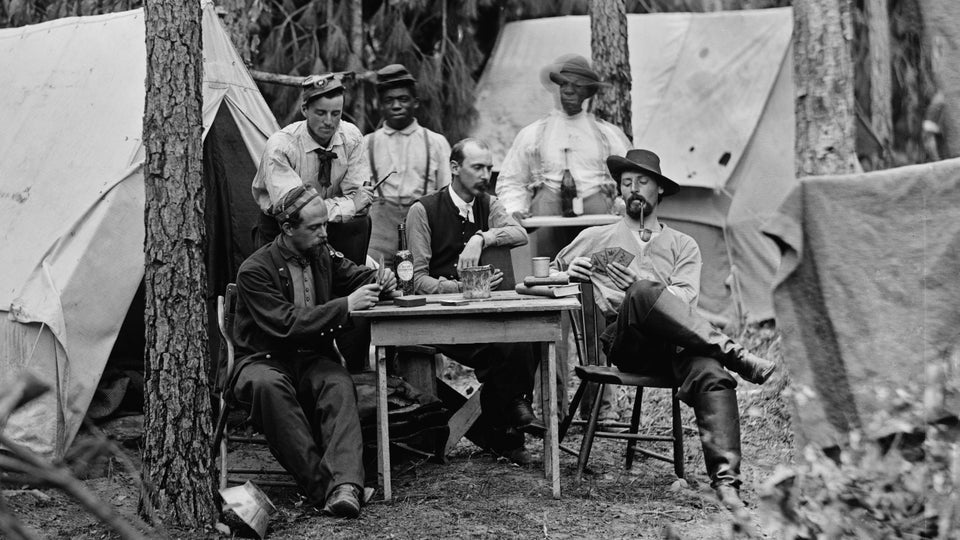

At the beginning of the war the army camps were breeding grounds for every type of immoral behavior. That has been common in the military throughout history, as soldiers (some as young as 12) recently out from under parental control threw off all restraints and dove into a sin-filled lifestyle in their attempt to demonstrate maturity.

► Drunkenness

► Drunken brawls—between officers as well as between rank and file soldiers

► Prostitution was legal and rampant; for instance, in Washington D.C. there were 450 brothels, and in nearby Alexandria, Virginia, there were over 75.

► Prostitutes followed the troops from one encampment to the next.

► Venereal disease was rampant, with the 183,000 cases in the Union Army alone.

► Pornography was available at that time.

► Novels of a sexual nature were in high demand.

► Gambling

► Brutality, rape, pillaging

► Profanity

Hugh White, a divinity student at Union Theological Seminary in Richmond, Virginia, had joined the 4th Virginia Regiment at the start of the war. He wrote home to his family explaining that his time in the army had only strengthened his belief in total human depravity.

Officers Playing Cards, Drinking Whiskey, Smoking

Suppression of Godliness

There was an ongoing effort made by chaplains and missionaries to disprove the widespread view that godly lifestyles would make a soldier effeminate or cowardly.

Idealism and Illusion

At the outset of the war, as the new recruits enlisted, there was an overwhelming sense of adventure and expectation for a glorious victory. There was the perverse thirst to rush into battle and “kill 20 Yankees before the war ended” in 90 days.

Illusion Destroyed

It wasn’t long before the young recruits had their illusions destroyed. The fatigue of military life, thousands dying from disease in the camps, inadequate clothing, homesickness, and the type of punishments measured out by officers, which previously were only administered to slaves (whipping, branding on the face, execution), woke these young men up to reality.

Christian in Name Only

Though almost all soldiers considered themselves “Christian,” and were familiar with Bible stories and themes, they could be simply described as being “backsliders.” One minister reported that out of three hundred men, he only found seven who were truly followers of Jesus Christ.

Radical Change

One account said that at the beginning of the war only 15% of most camps gave a semblance of Christianity. Toward the end of the war, in some regiments, there were only 15% that did not give evidence that Christ was ruling their lives. This was evidenced by attendance at church services and participation in Bible studies.

Deeper into Godlessness

The first major battle of the Civil War took place just north of Manassas, Virginia (Bull Run), on July 21, 1861. This was a Confederate victory, which elevated the pride and complacency of the Southern army.

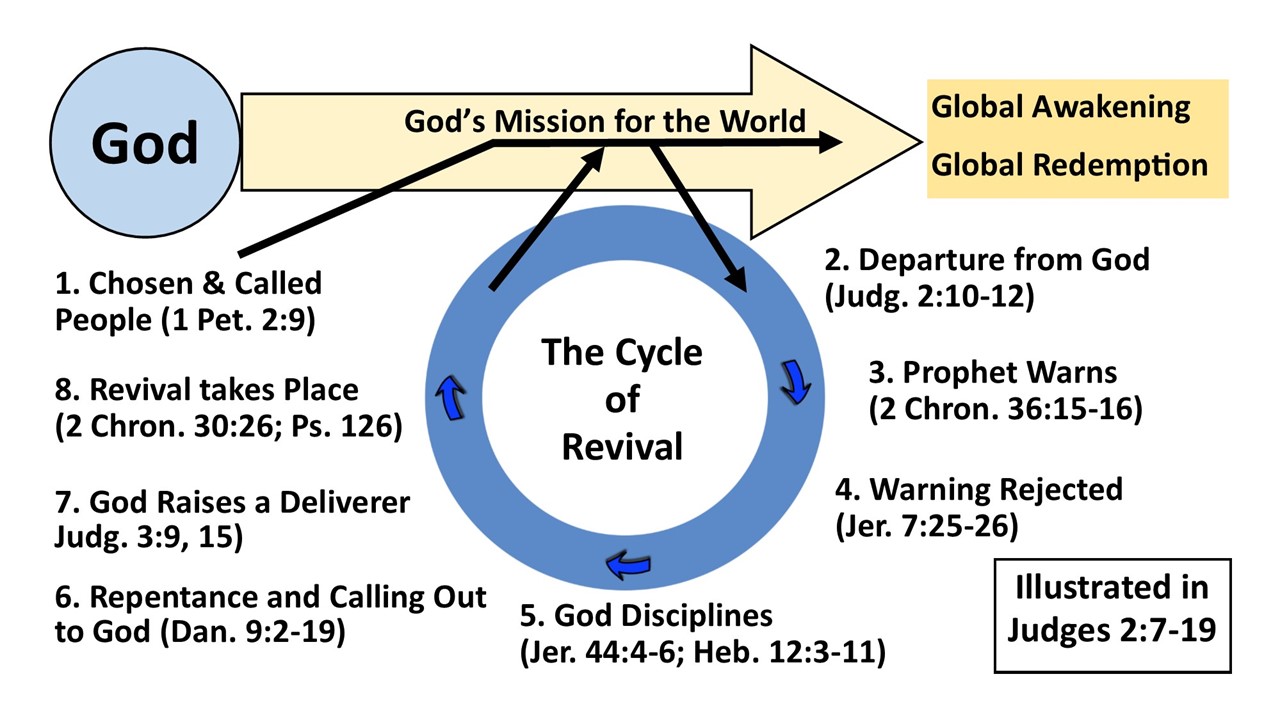

Throughout the Bible, and in Church history, we see a pattern of pride and complacency that led God’s people to turn their backs on Him and which actions plunged them deeply into various types of sin. As God sent prophets to warn, or when God disciplined His people, they would be shaken from their stupor, repent, and then turn back to Him. God would then forgive, restore and heal (2 Chronicles 7:13-14).

Biblical Pattern for Revival

____________

A chaplain at the time, J. William Jones, wrote that following the Confederate victory at Bull Run, the Confederate soldiers assumed they would crush the Union Army in a short period of time. When the end of the war wasn’t immediately seen,

► Inactivity in the war ensued and demoralization took over.

► Morals dropped further.

► The people of the South had previously been praying, but they now stopped, assuming the war was practically over.

► Greed of gain was a major curse in the South, as profiteers took advantage of the soldiers and the war effort. Pastors and the press began rebuking the people of the South for their personal selfishness, self-centeredness, and self-indulgence. While soldiers were suffering and dying in battles, hoarding and exploitation was taking place back home (price-gouging of business owners and merchants).

► Drunkenness in the camps became even more pronounced than before.

► Starvation was taking place in some areas, because distillers bought up the grain to make their 64,000 gallons of whiskey each day, with each of the hundreds of distillers having the possibility of earning $4,000 per day.

The chaplain of the 23rd North Carolina wrote for the North Carolina Baptist newspaper, the Biblical Recorder:

While Lincoln may slay his thousands, the liquor‑maker at home will slay his tens of thousands.

Absence of a Godly Presence

On May 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln ordered all regimental commanders in the Union Army to appoint chaplains for their units. Unfortunately for the Southern Army, this was not done. Though there may have been Confederate leadership that openly mentioned the name of God, they didn’t make a commitment for the establishment of chaplains for their soldiers. In the few exceptions where there was a chaplain, they didn’t have the official rank and status of their Union counterparts.

Several protestant denominations, determined to address the situation, sent colporteurs to distribute tracts and evangelize. They also sent civilian missionaries that worked alongside the chaplains.

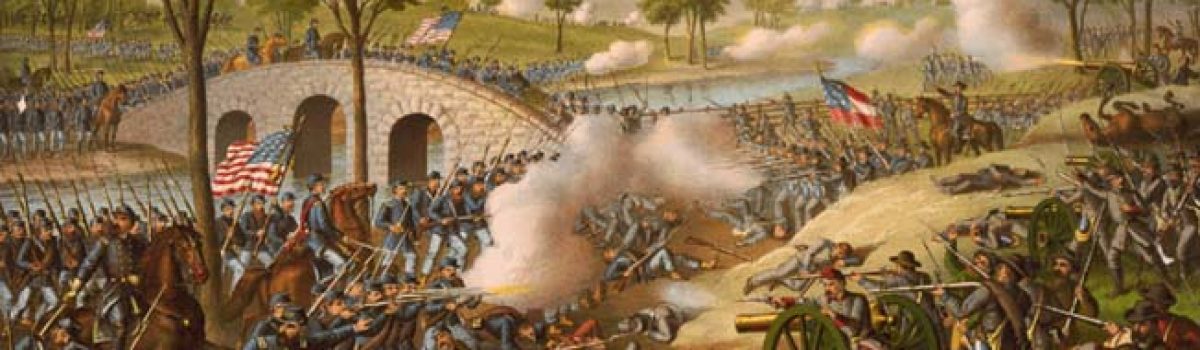

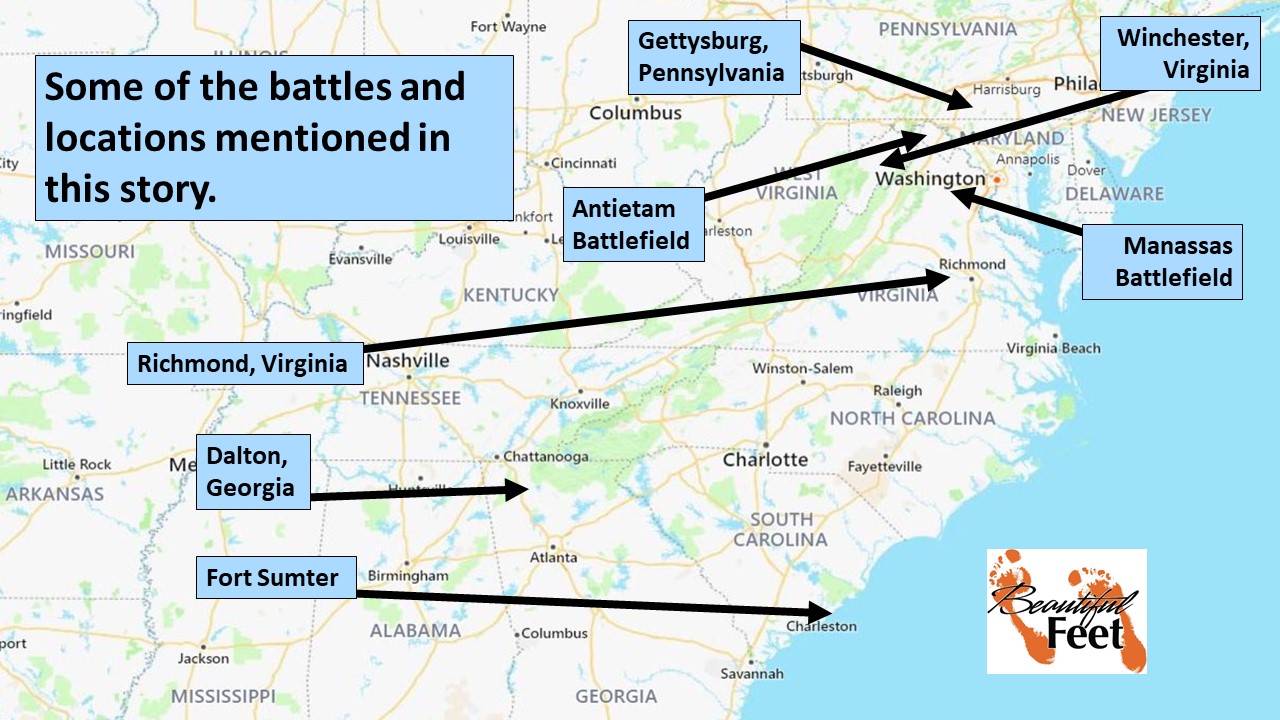

Antietam Battlefield – September 17, 1862

What Brought the South and the Confederate Soldiers to Their Knees in Prayer?

On September 17, 1862, Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia retreated in defeat from the Battle of Antietam/Sharpsburg to the Rappahannock River in northern Virginia. It was there that the soldiers bowed their knees in humility—which opened the windows of heaven for a powerful revival.

► The romantic and illusory thought of a quick victory had disappeared.

► A somber mood prevailed.

► After witnessing massive loss of lives, eternal concerns came to the forefront.

The chaplain J. William Jones, in his book, Christ in the Camp, wrote,

But when we came back from Sharpsburg to rest from a season amid the green fields and beautiful groves, and beside the streams of the lower Valley of Virginia, there began that series of revivals which went graciously and gloriously on until there had been over fifteen thousand professions of conversion in Lee’s Army, and there had been wrought a moral and religious revolution which those who did not witness it can scarcely appreciate.

The military defeats, coastal blockades, and other opposition began to strangle all communities throughout the south, and the economic pressure brought them to extraordinary prayer.

Sunrise Service (by Mort Kunstler)

Extraordinary Prayer

The dangers the South was being faced with, following the deaths of so many of their sons, led them to desperate prayer. They recognized they were greatly outnumbered and that their only source of help could be found in God.

Public fasts and prayers were ordered by the government and these took place frequently. Prayers were offered in churches and in homes. General John Gordon mentioned the following about the mothers praying at home as they worked:

Every click was a prayer; every stitch a tear.

Prayer meetings became common in the camps among the soldiers. The diaries, letters, and newspaper articles showed how common these prayers were. Though the prayers for ultimate victory went unanswered, the presence of the Holy Spirit began to move throughout the Southern Army.

The Development of the “Great Revival”

Though revivals took place throughout the duration of the war, it was during the fall of 1863 and through the spring and summer of 1864 that what was later called the “Great Revival” occurred. Although this event is best documented as having occurred in Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, it actually took place in both the Union, as well as the Confederate armies, throughout Virginia and Tennessee.

The revival was first witnessed among the South’s Army of Northern Virginia in September of 1862. Sometimes preaching and praying continued 24 hours a day, and chapels couldn’t hold the soldiers who wanted to get inside.

J. William Jones, a chaplain in the Army of Northern Virginia, says the following about this revival:

But any history of that army which omits an account of the wonderful influence of religion upon it—which fails to tell how the courage, discipline and morale of the whole was influenced by the humble piety and evangelical zeal of many of its officers and men—would be incomplete and unsatisfactory.

There was such a change that Rev J. M. Stokes, chaplain of Wright’s Georgia Brigade wrote:

There is less profanity in a week now, than there was in a day six months ago. And I am quite sure there are ten who attend religious services now to one who attended six months ago.

There were two sweeping and prolonged revivals that the Army of Northern Virginia experienced.

FIRST—along the Rappahannock River in the Fredericksburg, Virginia area, from September 1862 until May 1863.

SECOND—From August 1863 (after the July 1-3 Gettysburg Campaign) until May 1864 along the Rapidan River near Orange Court House, Virginia.

Several ministers mentioned the following of the work of God among the soldiers:

The whole army is a vast field, ready and ripe to the harvest, and all the reapers have to do is go in and reap from end to end. The susceptibility of the soldiery to the Gospel is wonderful, and, doubtful as the remark may appear, the military camp is most favorable to the work of revival. The soldiers, with the simplicity of little children, listen to and embrace the truth.

Yesterday evening Brother Pritchard baptized seventeen in the Rapidan [River], in sight of the enemy’s pickets, who looked on as though they took some interest in the proceeding.

God is wonderfully reviving his work here, and throughout the army. Congregations large–interest almost universal. In our chaplains’ meeting it was thought, with imperfect statistics, that about five hundred were converted every week.

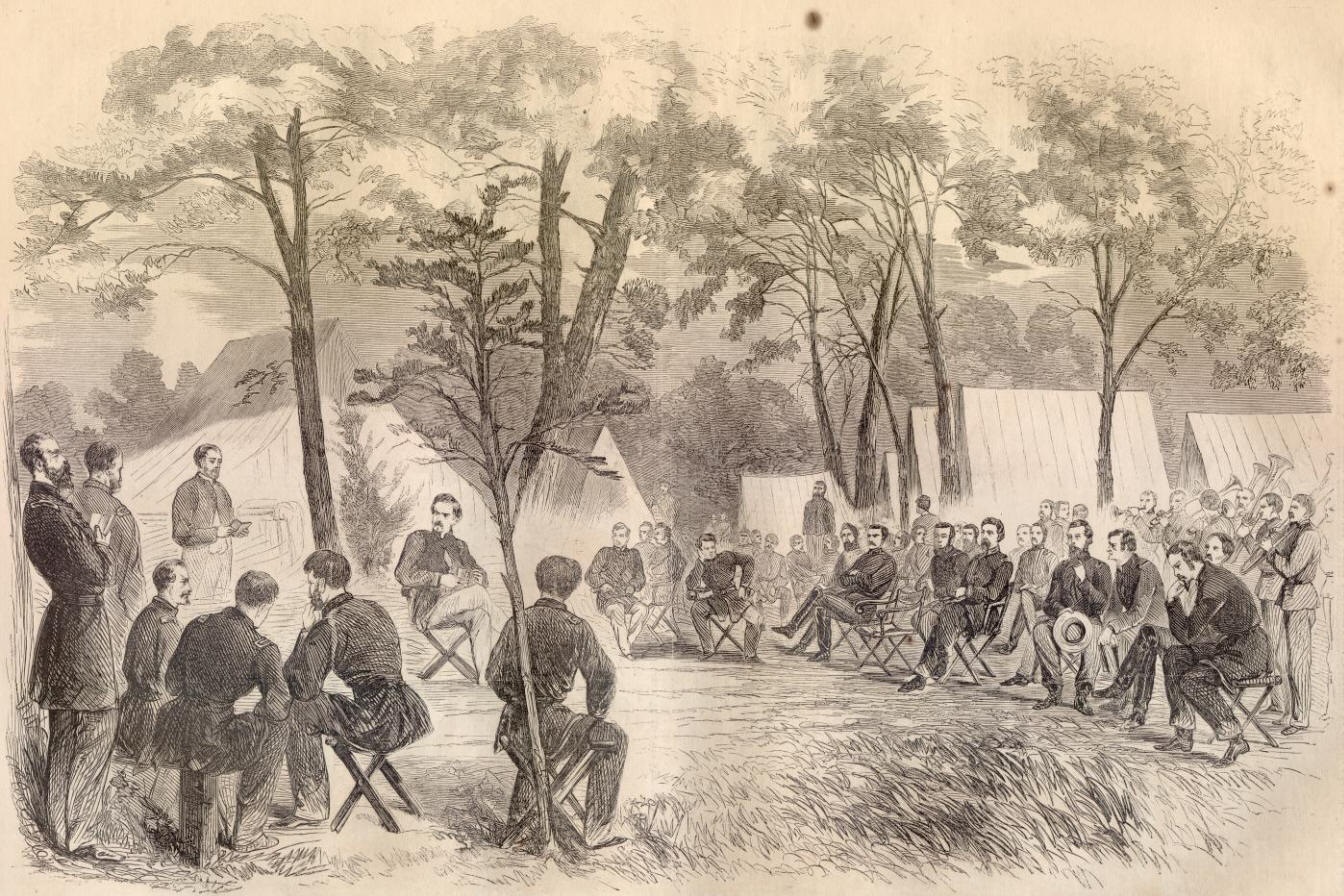

Church service at General McClellan’s Head Quarters

Harpers Weekly: August 16, 1862

During these extended times of revival:

► Large crowds of soldiers gathered often, with chapels too small for the gathered crowds.

► Sometimes preaching and prayer continued 24 hours per day.

► The Union Army was experiencing revivals at the same time.

► Large numbers made a profession of their faith in Christ.

► There was a large demand for tracts and Bibles.

► Lifestyle changes were clearly witnessed as sin was repented of.

► As reports of more defeats would come in from other locations, the Army of Northern Virginia became even more introspective, humble, and repentant.

Here are a few comments from ministers who were preaching near the Rappahannock River camp on October 12, 1862,

The men listened with the deepest attention, and seemed very reluctant to leave the ground when the benediction was pronounced.

Early in October while the army was camped near Winchester, there were evident signs of a deep awakening among the troops.

The men were deeply impressed by the dangers they had escaped, and their hearts were open to receive the truth.

John H. Worsham, a soldier in the 21st Virginia Infantry, gives us a picture of the typical outdoor revival setting,

Trees were cut from the adjoining woods, rolled to this spot, and arranged for seating of at least 2,000 people. At the lower end a platform was raised with logs, rough boards were placed on them, and a bench was made at the far side for the seating of preachers. In front was a pulpit, or desk, made from a box. Around this platform and around the seats, stakes were driven into the ground about ten or fifteen feet apart. On top of them were placed baskets of iron wire, iron hoops, etc. Into these baskets were placed chunks of light wood, and at night they were lighted and threw a red glare far beyond the confines of the place of worship.

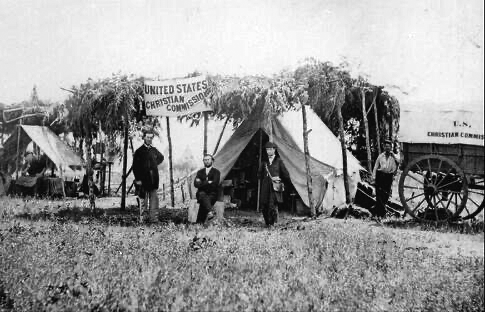

Tent and Carriage of the United States Christian Commission

In addition to providing religious literature for the Union, the United States Christian Commission was involved in a multitude of social services. They supplied medical services, provided supplies and social workers, and also assisted the U.S. Sanitary Commission.

New Appreciation for Chaplains and Missionaries

The attitude of the officers changed dramatically toward the revival movement. Whether they were godly men or not, the colonels knew that Christian men were more loyal than others, more faithful, honest, and less susceptible to destructive sinful behavior. They also knew that there was a tremendous amount of comfort the soldiers received from the ministers. Chaplains became the morale of the army.

It is impossible to quantify the value of such [chaplain] service. How can we establish the worth of a bereaved family’s comfort in the knowledge that a son, husband, father, or brother had been comforted at death and accorded a Christian or religious burial…We simply cannot measure such intangible service, yet only the most cynical among us would deny the contribution…in a very real sense [chaplains were] the morale of the army.

General Stonewall Jackson wrote the following to the Southern Presbyterian General Assembly pleading for chaplains who preached the gospel:

Every branch of the Christian Church should send into the army some of its most prominent ministers who are distinguished for their piety, talents, and zeal; . . . . Denominational distinctions should be kept out of view, and not touched upon. And, as a general rule, I do not think that a chaplain who would preach denominational sermons should be in the army. His congregation is his regiment, and it is composed of various denominations. I would like to see no question asked in the army of what denomination a chaplain belongs to; but let the question be, does he preach the gospel?”

Prayer in General “Stonewall” Jackson’s Camp

Literature and Bibles

There was a huge demand for religious literature.

► Bibles and partial testaments

► Hymns and prayer books

► Reading clubs were formed to share materials and Bibles

When it came time for distribution of literature, men nearly trampled one another to get a copy. Through the revival, millions of testaments and many millions of copies of sermons and tracts were distributed, along with many booklets, and there was never enough to meet the demand.

One soldier, who was grateful for the Bible he received, wrote:

I had my Bible in my right breast pocket, and a ball struck it and bounced back. It would have made a severe wound but for the Bible.

About the demand for literature, chaplain William W. Bennett wrote:

Oh, it is affecting to see the soldiers crowd and press about the preacher for want of tracts, etc., he has to distribute, and it is sad to see hundreds retiring without being supplied!

I never saw men who were better prepared to receive religious instruction and advice. … The dying begged for our prayers and our songs. Every evening we would gather around the wounded and sing and pray with them. Many wounded, who had hitherto led wicked lives, became entirely changed.

Records of Published Materials

At the height of the revival, chaplain J. William Jones estimated that there were one million pages of tracts distributed a week.

Most Famous Tract

“A Mother’s Parting Words to Her Soldier Boy”

Revival at Hospitals

One who visited the hospital in Richmond, Virginia, wrote,

The field of labor opened here for the accomplishment of good is beyond measure… At 3:00 o’clock services were held in the main hall of the hospital. It was a most imposing spectacle to see men in all stages of sickness—some sitting upon their beds, while others were laying down listening to the word of God—many of them probably for the last time. I do not think I ever saw a more attentive audience.

Another chaplain, at the Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond, Virginia, wrote,

No sight could be more touching than to stand near the chapel and see the wounded and the pale convalescents hobbling and creeping to the place of worship at the sound of the bell.

Preaching and Other Roles of Chaplains, Missionaries, and Pastors

No matter where a minister preached, and no matter what his name, as soon as the word got out that there was to be a sermon, a large crowd would immediately gather, eager to listen.

In addition to the opportunities to preach, the chaplains and missionaries would also

► Hold Bible classes

► Teach reading classes

► Help form “Christian Associations” to strengthen converts within a brigade

► Maintain camp libraries

► Care for the dead and perform funerals

► Provide spiritual ministry to those who today would be diagnosed with PTSD

► Serve as carpenters, nurses, gunrunners, as well as soldiers

It was estimated that there were 1,000-1,300 men who served as chaplains in the Southern Army.

Lined up for baptisms in the river

Church Buildings and Services

When troops set up camps in the winter of 1863-1864, they would erect large log churches that would seat from 300-500 soldiers. To meet this demand for places of worship, 37 structures were erected along the Rapidan River, one every 600-800 yards. Churches accommodating 2,000 worshipers were often too small.

The greatest revival swept through the camps on the return of the army from Gettysburg and resulted in thousands of conversions. During the winter of 1864‑65, there were over sixty log chapels in the Richmond and Petersburg lines.

Concerning the hunger for more of God, soldiers would be seen running from regiments two miles away so they could get a seat for a chapel service. And after having arrived, they would pack the churches like “herring in a barrel.”

During a six-week lull in the fighting in Virginia during the summer of 1864, one brigade chaplain scheduled daily prayers at sunrise, an “inquiry meeting” each morning at eight, preaching at eleven, prayers again at four, then preaching at night.

J. William Jones indicated that at times he would conduct,

…three to five [religious] meetings a day, which resulted in about fifty professions of conversion, most of whom … [were] baptized in a pond which was exposed to the enemy’s fire, and where several men were wounded while the ordinance was being administered.

In one soldier’s diary we read:

We sometimes feel more as if we were in a camp-meeting than in the army expecting to meet an enemy.

A soldier who wanted nothing to do with the revival, in a letter to his wife wrote:

It seems to me that whereever [sic] I go I can never get rid of the Psalm-singers.

So common were the conversions, that one captain wrote in in his diary [mid-1863],

Today is Sunday. Nothing unusual… preaching in the afternoon and evening. Many joined the church.

Longing for Mothers

During one prayer meeting, a young soldier yelled out;

O that my mother were here! … she has so long been praying for me, and now I have found the Savior.

Another wounded Christian soldier asked a friend to,

Tell my mother that I read my Testament and put all my trust in the Lord….I am not afraid to die.

Denominational Walls Were Down

In the Confederate army, sectarianism was nonexistent. Chaplains, colporteurs, and missionaries all worked together from all evangelical denominations. Dr. William J. Hoge wrote about an incident at Fredericksburg in the spring of 1863 with Barksdale’s Mississippi Brigade:

We had a Presbyterian sermon, introduced by Baptist services, under the direction of a Methodist chaplain, in an Episcopal church.

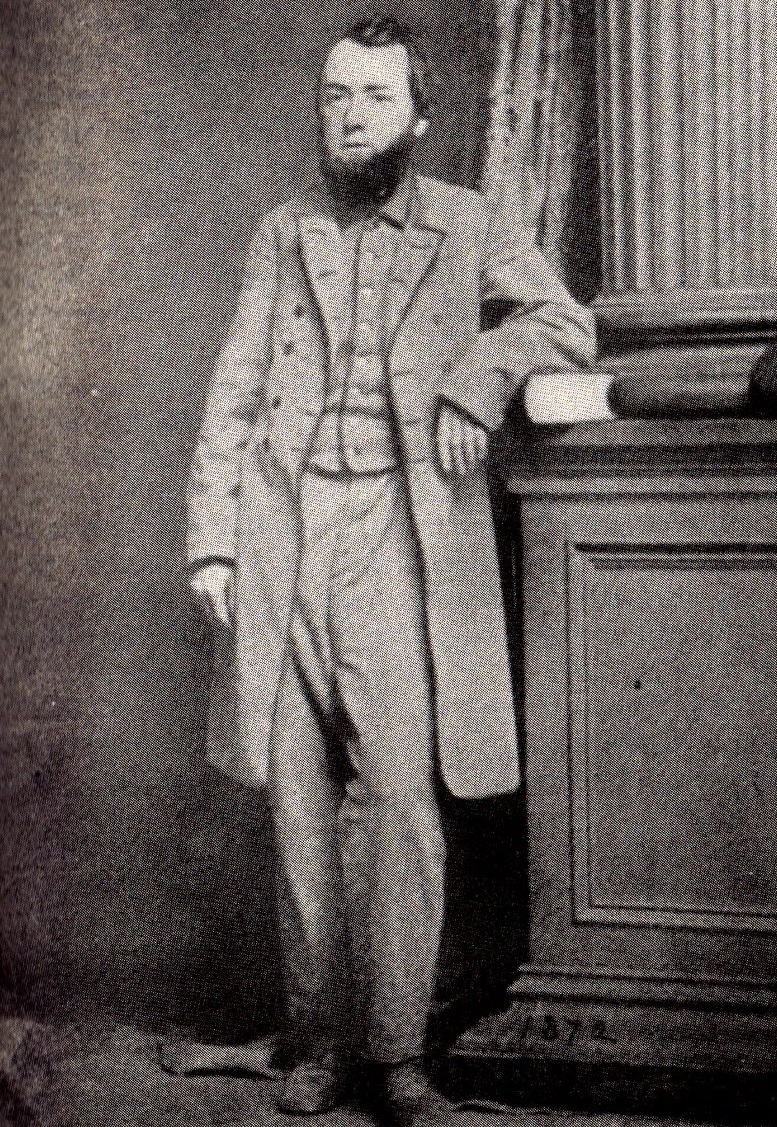

J. William Jones, Chaplain of 13th Virginia Regiment. He is one of the main chroniclers of the Great Revival.

Revival in the Union Army

Though there were significant revivals that did occur among Union troops, it was nothing comparable to the South. Lincoln, commenting on the disparity, said:

Rebel soldiers are praying with a great deal more earnestness…than our own troops…

Results of the Revival

► There had been 150,000 new conversions in the Confederate Army by January 1865.

► Some chaplains estimated that over 250,000 men in the Confederate Armies were converted during the war.

► Between 20,000 and 30,000 conversions occurred in the Army of Tennessee while it was at Dalton, Georgia, in 1863-1864. These added to the ranks of the many devout Christians who brought their faith to the army. Some estimated that fully one-third of all Confederate soldiers in the field were “praying church-members” at the end of the war.

► The aftereffects of this great revival continued for many decades after the war.

► Even the press became a communication tool of evangelists and pastors. According to the August 10, 1863, edition of the Richmond Daily Dispatch,

A revival of religion is now progressing in the 46th Va., under the ministration of Rev. W. Gaines Miller, the Chaplain, and also in other regiments of Wise’s brigade. There have been over 50 professions of conversion in that regiment, 170 in the 26th Va., and a number in the 4th Va. heavy artillery, at Chaffin’s Bluff.

► Conversions took place among all ranks in the military—including generals.

- General Bell Hood, crippled from multiple battlefield wounds, was baptized in the fall of 1864. Henry Lay, Episcopal bishop of Arkansas, describes the scene:

Unable to kneel, [General Hood] supported himself on his crutch and staff, and with bowed head received the benediction.

- Arthur Lyon Fremantle stated that he witnessed the baptism of General Braxton Bragg at the field quarters of General Polk.

- General Ambrose P. Hill was led to the Lord on the field of Second Manassas by his commander General Stonewall Jackson.

- General Joseph Eggleston Johnston

- General William Joseph Hardee

► The conversions were not merely “Battle-Field Conversions” that were temporary and fleeting. Evidence of this is proven by J. William Jones two years after the conclusion of the war.

In 1867 I addressed letters to all of the college presidents, and many of the leading pastors in the South, in order to ascertain how far our returned soldiers were maintaining their Christian profession, and what proportion of them were preparing for the Gospel ministry.

Their replies were in the highest degree satisfactory and gratifying, showing that about four-fifths of the Christian students of our colleges had been in the army, and that a large proportion of them had found Christ in the camp—that nine-tenths of the candidates for the ministry had determined to preach while in the army—and nearly all of the army converts were maintaining their profession, many of them pillars in the church.

One of Many Soldiers Who Became Ministers After the War

Lieutenant George W. Finley, 56th Virginia Infantry. Finley was captured on July 3, 1863 at Gettysburg and imprisoned until May 14, 1865. During his imprisonment he decided to become a minister if he survived. He made good on his pledge and eventually became a Presbyterian pastor.

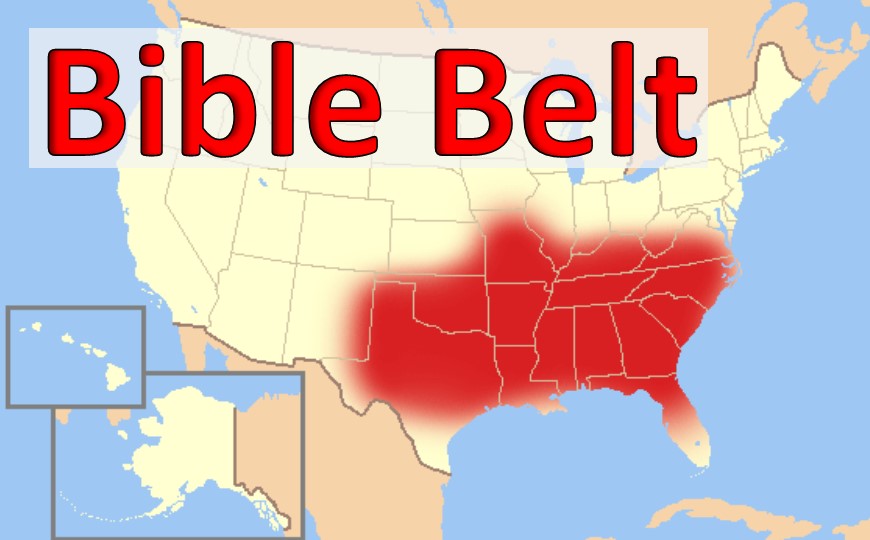

Bible Belt is a name given to the southeastern quarter of the United States. The many thousands of Christian soldiers returning from the war were undoubtedly a significant reason why that region received that name.

Sources

► Christ in the Camp by J. William Jones

► Christian Soldiers: The Meaning of Revivalism in the Confederate Army by Drew Faust

► Desertion, Cowardice and Punishment by Mark A. Weitz

► Religion During the Civil War by Charles F. Irons

► Religious Revival in Civil War Armies by Gordon Leidner

► Reports of the Revival by Gardiner H. Shattuck, Jr.

► Sex in the Civil War by Wikipedia

► The Great Harvest: Revival in the Confederate Army During the Civil War by Mark Summers

► The Great Revival in the Southern Armies by William W. Bennett

► The Great Revival of 1863 by Troy D. Harman

► The Revival in the Confederate Army in the Civil War by Malcolm Nicholson

► Revival in the Southern Army by Richard Lee Montgomery

► Revivalism in the Confederate Armies by Herman Norton

► The Second Evangelical Awakening in America by J. Edwin Orr

► United States Christian Commission by Wikipedia

► Video: Confederate Revival in the American Civil War by Truth in History

Return to List of Revival Stories

Chet & Phyllis Swearingen

(260) 920-8248

romans1015@outlook.com

Beautiful Feet

P.O. Box 915

Auburn, IN 46706