Background Information

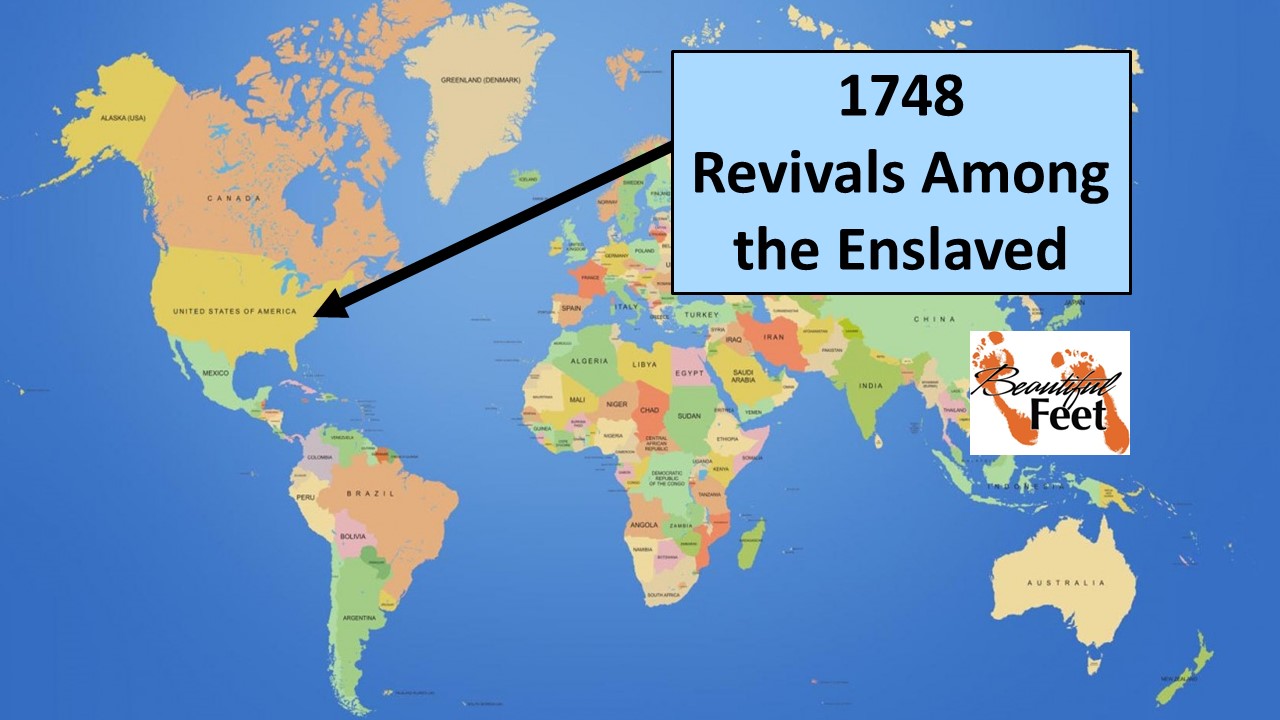

The First Great Awakening occurred during the 1730s – 1740s, but documents reveal that the Gospel continued to spread through the New England American colonies following the 1740s.

With this revival account, we will build on separate revival accounts, such as the 1743 Virginia Revivals. In this account we share about the revivals that touched other parts of Virginia and extended down into South Carolina, specifically pointing out the impact revival had on the enslaved blacks.

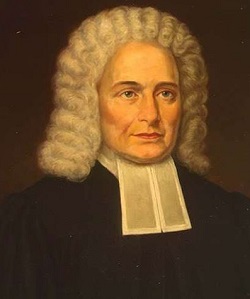

Samuel Davies: 4th President of

Princeton University

Samuel Davies

The man focused on in this revival account is the Rev. Samuel Davies. It is from his letters that most of our information came.

Church of England’s Official Status

From 1619, the Church of England was the formal and official religion in the colony of Virginia. It remained so until after the American Revolution. This official status placed restrictions on all other Christian denominations from operating in the colony.

Puritans and Other Denominations

Those from England who did not comply with the Church of England, and who were persecuted in various ways through the years, were known as Dissenters or Nonconformists. In 1747, the 23-year-old Samuel Davies, being newly commissioned as an evangelist by the New Castle, Delaware, Presbytery, was sent to Virginia to minister to the dissenting settlers.

In October 1748, Davies was sent, not as an evangelist, but to become a pastor to the settlers in Hanover, Virginia, since that was the area that had the highest number of Presbyterian settlers, all without a Presbyterian minister.

Upon his arrival, Davies took the responsibility for ministering to the people at four different meetinghouses (churches), approximately 15-20 miles apart from each other, with the total number reaching close to 500 people. On some occasions that number would double.

Davies initially assumed that the large number of people gathering were out of curiosity about this new minister, but as time went on, and attendance didn’t decrease, he realized that something special was taking place.

In addition to the four meetinghouses, he was also called upon to preach in locations up to 45 miles away, none of which had dissenting churches. One such location was Essex.

Report on the Enslaved

In Davies’ letter dated April 1758, he mentioned that he had baptized about “six adult Negroes.” He also said that there were another six under examination—in preparation to be baptized. He mentioned that these individuals were “as eager as ever to learn to read.” Davies provided them with books to aid them in that regard.

Writing on August 30, 1758, Davies said that he had become very sick during a three-day journey, having been exposed to the elements for most of the time. But even with the sickness, he said that he

…preached with more spiritual dexterity, engagedness, and solemnity than ever I did in my life before, and the effect was answerable.

He continues in his letter informing the recipient that from May till the middle of June 1758, 130 people were converted. Of those, there were about “twenty Ethiopians.”

Davies also reported on the exemplary lifestyles of the black believers with these words:

The black communicants are as eminent Christians as I have in my congregation: had I time to relate to you the exercises of the most savage boy of them, you would not only be pleased but transported.

When Davies informed the congregation that he had books he wanted to distribute, over 70 blacks came to him, desperately desiring them:

And they were like to quarrel with me and one another for more books.

Upon hearing that the people in England provided these books for them, these believers were lifted out of their spiritual lethargy and led to diligent efforts to read the Bible on their own.

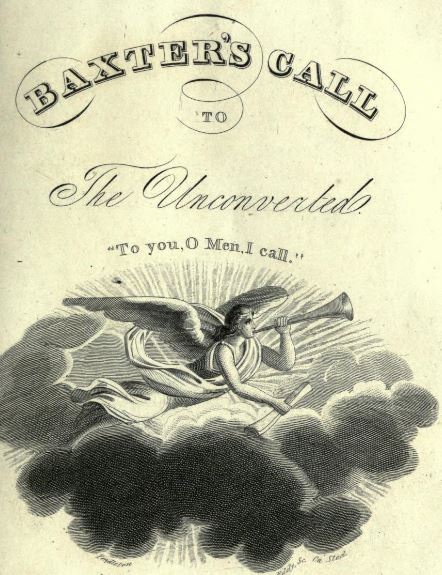

Richard Baxter’s: “A Call to the Unconverted” was credited with having led to the conversion of hundreds. About that book, Davies said:

…it at once mortifies and pleases me, that, in more instances than these, GOD has as it were taken the work out of my hand, and blessed the endeavors of good men four thousand miles off, for the conversion of sinners while my feeble addresses to them has had little or no effect.

John Reynold’s “A Compassionate Address”

was used as a textbook to teach

blacks and poor whites how to read.

Singing of Blacks in the Balcony

As the blacks were given spelling books and taught to read, they made good use of Isaac Watts’ “The Psalms and Hymns,” as well as Reynolds’ “A Compassionate Address.” During church services, as Davies would direct them to a certain page in the hymnal, these enslaved would turn there, and:

Then all breaking out in a torrent of sacred harmony, enough to bear away the whole congregation to heaven.

The poor white families were also said to have greatly benefited from the books donated by the British Bible Society.

Blacks at the Communion Table

Davies remarked about the seriousness of the enslaved as they participated in the communion services:

What joy, what transport would it afford the truly pious among you, to see a goodly number of these poor Africans sit down at a sacramental table! not like frozen formalists, but like affectionate, serious Christians, unable to rise up from a table appointed to commemorate a Redeemer’s love, with dry eyes!

Blacks Conducted Small Group Bible Study

Some of the blacks would meet during the week to read the Bible together, sing, and read from other books as well. They were continually pleading with Davies for more books.

Revival Switched from Whites to Blacks

In a letter dated November 1759, a minister from Cumberland County, Virginia, wrote that the revival among the whites had slowed down, and then picked up among the blacks. With the outpouring of the Spirit among the blacks, they had little time left to the studying of the English language:

The Lord has opened the windows of heaven over Virginia, and poured blessings till there is no room to receive them! I never saw such a plentiful harvest in Virginia of every kind: This you see will oblige not only the slaves, but the whites to be continually engaged; therefore can get no time to learn their books.

What marvelous things has God done for us in America, and consequently for you in Great Britain! With what irrefutable rapidity did our conquests go on!

In a letter dated August 7, 1760, Rev. Mr. Todd, a minister in Hanover County, Virginia, mentions the following about the spread of the revival:

► Gratitude to the English Bible Society for the books and literature received, as they were influential in the spread of the revival.

► Hundreds of blacks, in addition to whites, can now read and spell, “who a few years ago did not know one letter.”

► Many had been converted and left their former sinful lifestyles.

► They would walk up to 12 miles to attend services or receive private instructions from their minister.

► The Bibles, prayer books, catechisms, hymnals, and spelling and reading books, supplied by the English Bible Society, were very instrumental in the spreading of the revival.

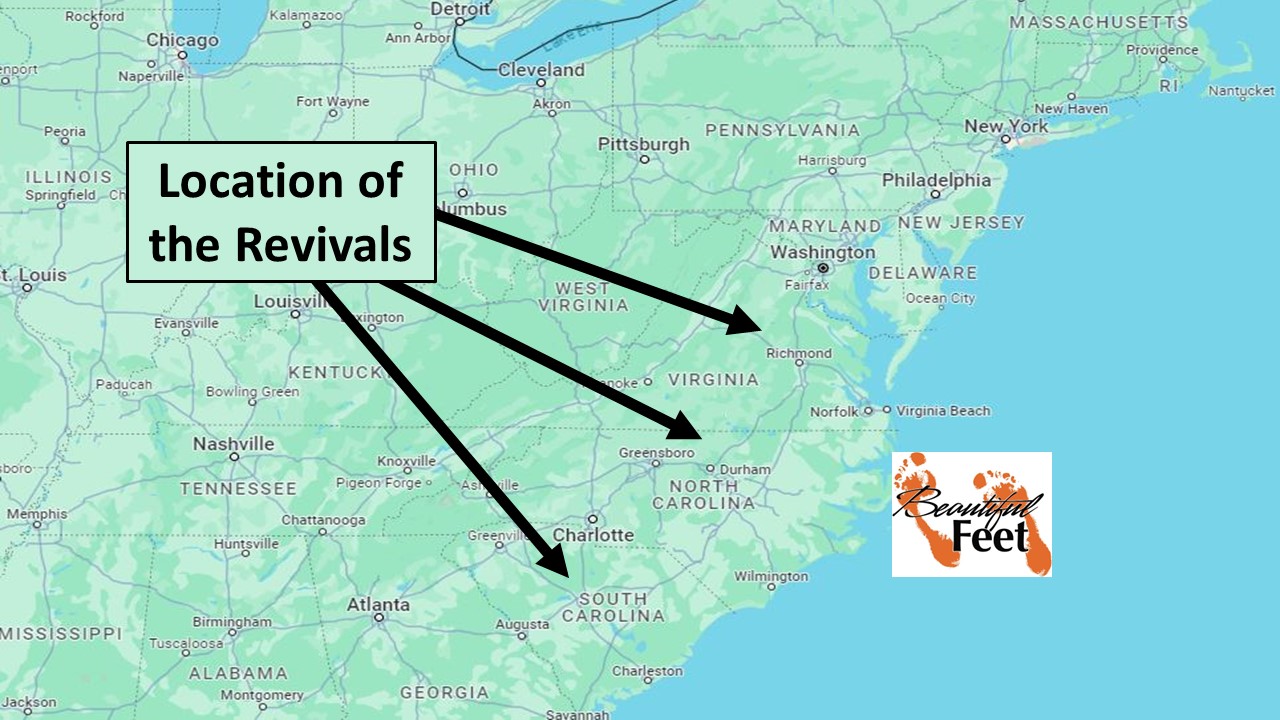

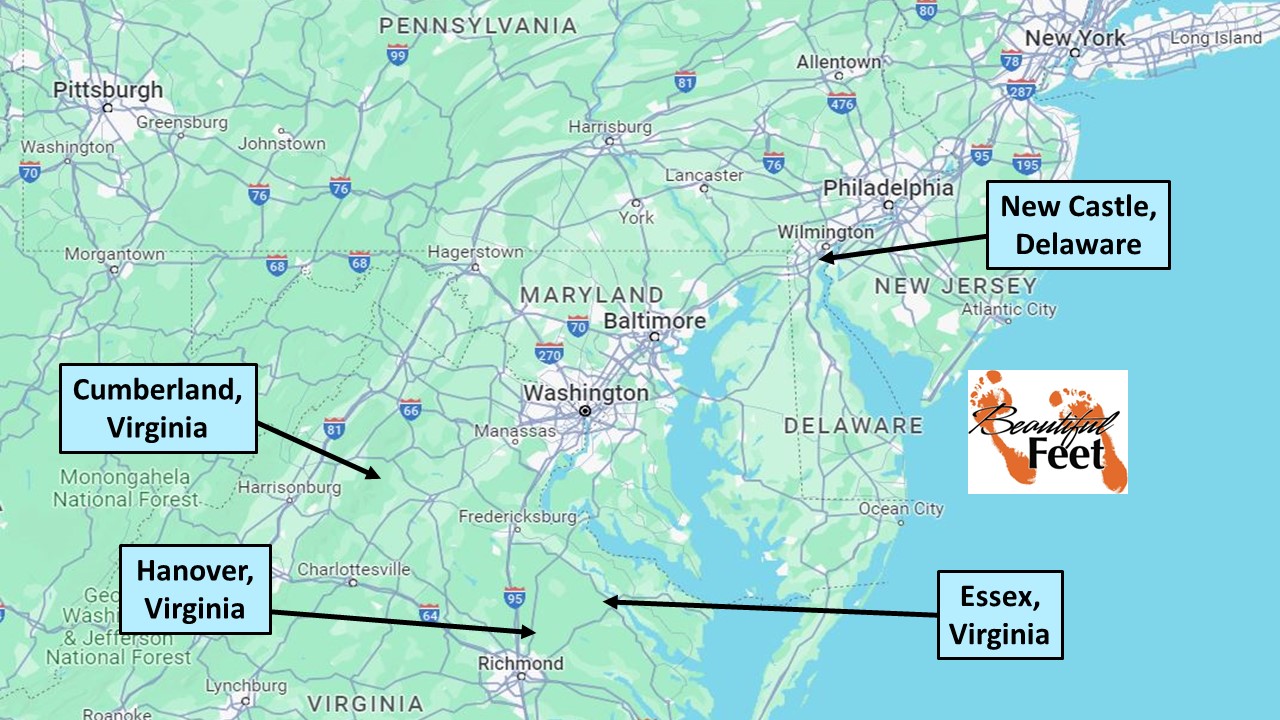

Locations of some of the areas influenced by the revival

Revival in Cumberland County

In a letter dated January 6, 1761, Rev. Mr. Wright, a minister in Cumberland County, Virginia, wrote to the English Bible Society, thanking them for the generous contribution of Bibles, books, hymns, and reading resources for the blacks and poor whites in Virginia. In his letter he stated that:

► He arrived in Cumberland County in November 1755.

► At the time, there were only about 5 Christians in the area.

► By the following July, 100 had joined the church.

► After another 13 months, 90 more joined.

► Every year since then, about 80 more joined the church (possibly 320 total).

Due to the large number of books donated by the Bible Society, many of which were given to the Ethiopians (blacks), Wright said:

Ethiopia has stretched out her hands to God beyond my most sanguine expectations.

And now I can tell you, to the joy of all the upright in heart; that I have baptized, as near as I can guess, between sixty and seventy [blacks], old and young.

It would charm your hearts to behold their seriousness and behavior; but especially to hear their religious experience of God’s grace upon their minds: their abasing sense of the vileness of their hearts; their deep humility, and strenuous endeavors after holiness, and very surprising; and indeed beyond the whites who are truly godly, as far as I can judge.

Overview of the Revival, Written by Rev. Mr. Wright

Thus I have given you a general idea of Religion here, and was I to tell you of my baptizing four or five Quakers, and the religious experiences and exercises of multitudes, it would edify and surprise you. Together with the alteration made in families and neighborhoods, and the spread of Religion into neighboring counties; I am persuaded future generations, as well as this, will look upon it to be matter of wonder and praise to the Lord Jesus!

Glimpse of Revival in South Carolina

We conclude this account with a brief bit of information about the revival as it was found in the colony (Province) of South Carolina.

In a letter dated May 21, 1761, written by Rev. Mr. Richardson from South Carolina, he indicated that:

► Over 100 had joined the church since last October.

► The need for ministers was great, as there were only two of them in an area 300 miles by 500 miles.

Sources

► A Call to the Unconverted by Richard Baxter

► A Compassionate Address to the Christian World by John Reynolds

► Letters from the Rev. Samuel Davies, and others by Samuel Davies

► History of Slavery in Virginia by Wikipedia

► Samuel Davies by Britannica

► Samuel Davies by Wikipedia

► Slavery in the Colonial History of the United States by Wikipedia

► The Psalms and Hymns of Rev. Isaac Watts, D.D. by Rev. John Rippon

► The First Catechism (for children) by Isaac Watts

Return to List of Revival Stories

Chet & Phyllis Swearingen:

Office: (260) 920-8248

romans1015@outlook.com

Beautiful Feet

P.O. Box 915

Auburn, IN 46706